Changing the Narrative Around Prison Reform – Part 1

Changing the Narrative Around Prison Reform – Part 1

Read time – 6 ½ minutes.

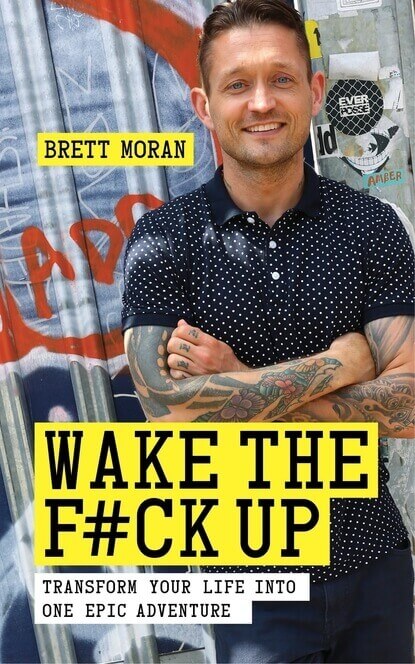

My best friend—Brett Moran—is a reformed prison convict with an incredible story of transformation.

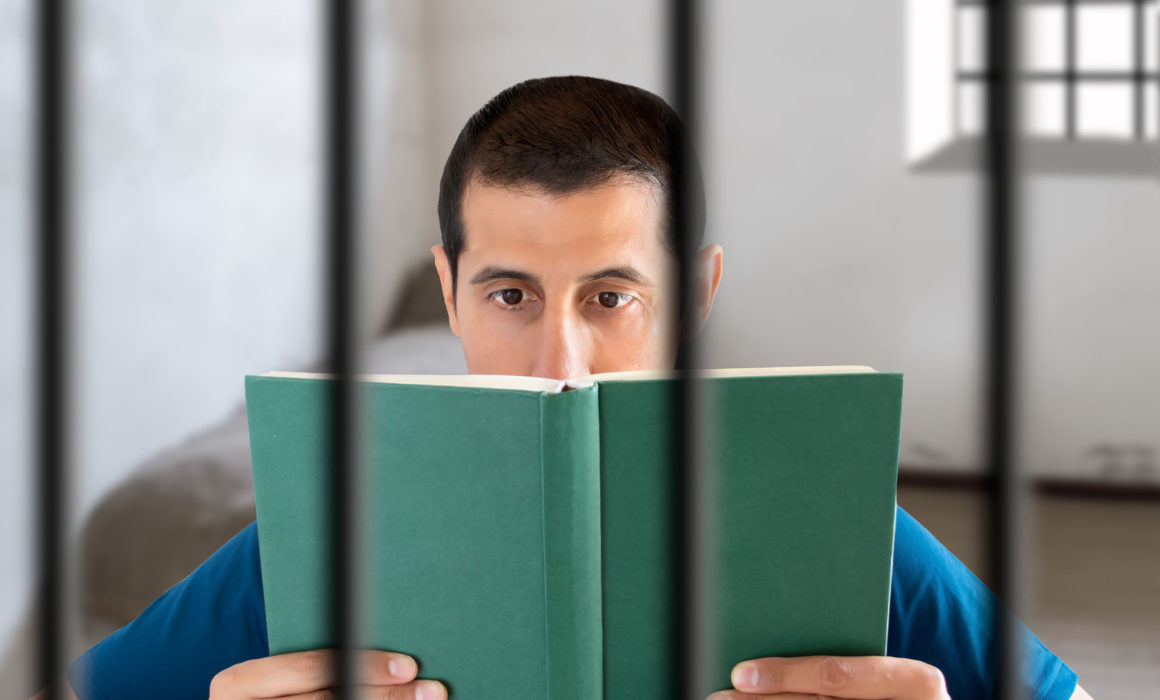

As a crack dealer and addict, he went to prison on a driving offense, and carried on his drug habit inside. One day in the prison library he picked up a book on Buddhism to cover up a drug deal. He started reading it and something inside him broke open. He took the book back to his cell, continuing reading it under his bed covers with a flashlight, so his cellmate wouldn’t see him.

It was the start of an awakening that led him to be an authentic, down-to-earth, spiritual teacher who is tattooed from head to toe, and author of the no-nonsense transformation book Wake the F#ck Up.

Whether he is inspiring prisoners or everyday people with the understanding that change is possible, there is no space to argue with what he shares, because he is a living example of his own teachings.

US Prison Reform

Prison reform is a hot topic at present, and covers not only trying to reduce the amount of people sent to jail in the US, but also how we can help them bounce back when they are released. The more I come to understand the US prison system, the more convinced I am that a story like Brett’s would have been far less likely if he lived here in the US, and not in the UK where he comes from (especially as in some parts of the US, prisoners aren’t allowed access to books).

Since I moved to the United States, I started to understand that there is a huge disparity between the way previous convicts are reintegrated into society in European countries, as opposed to the opportunities they receive here. But there are also recent moves to break down these disparities and create more promising paths for reformation within the prison system.

This week we’re going to focus on one aspect of prison reform—how we change the social narrative around those who have been incarcerated so we can think and talk about them differently, creating a more promising pathway for reintegration—and in next weeks post, we’ll be looking at how we begin changing the narrative around the prison system as a whole.

“Tagged and Going Down”

My own passion for prison reform dates back almost two decades to when I was teaching teenagers with severe behavioral issues. Before anyone was really talking about intersectionality, the socio-economic factors related to the likelihood of imprisonment, and the unfair racial biasing in prison sentencing, I was part of a cutting-edge team in the UK, working with young people to try and prevent them from being incarcerated.

In England a system of “tagging” was popular at that time, which meant that the last stop before prison was an ankle monitor that would act as a tool to curfew young people after 7pm.

These kids were referred to as “tagged and going down” (“going down” being the British slang used for someone who is about to enter the prison system). I worked with these young people for a number of years, using drama as a social and educational tool to help them explore the consequences of their choices, in an attempt to keep them from making that final choice which would potentially lead to their incarceration.

What I noticed was that there was already a social narrative around these young people, and an expectation of their “path to self-destruction.” The dialogue around them already had them labelled as “a lost cause” or “an inevitability.” I saw it as my job not only to help them rewrite their own story, but to change the narrative of those around them who had already marked them with certain expectations.

Good Versus Evil

We don’t just need to change our narrative around those who have a greater chance of being incarcerated. We need to change our dialogue around every aspect of prison reform too. Part of this shift lies in a deeply embedded Western narrative around good versus evil. In Western cultures—especially those who have been raised on a Hollywood diet of villains versus heroes—there can be a tendency to judge a person’s core character based on their past actions. This has been reinforced in the dialogue around incarceration. The ‘bad guy’ who ‘did wrong’ becomes a second class citizen, and there are very few opportunities built into that narrative for the average person on the street who committed a crime to reintegrate successfully.

One of the core issues is that often, when someone has committed a crime, it is viewed in isolation, rather than as being symptomatic of a whole host of inter-related socio-economic issues that created a chain of events leading to that crime. If we are thinking about prison reform, we first need to think about the context in which crimes are often committed rather than polarizing our thinking into good versus evil.

We need to be creating opportunities for those who have been incarcerated to break out of socio-cultural conditioning and actually reform in prisons. They need to be places of education and growth, and this is slowly being recognized in some parts of the US. For example, there is a movement to reverse the outdated law that keeps books from prisoners. In the latest news, Pennsylvania correction agency have just announced that they are allowing books in prisons.

This is a huge step because if we want to support someone to change their perspective, see the world through different eyes, or take a different path, it’s often going to require some kind of outside influence, such as we saw in the opening of this article with Brett Moran in the prison library.

Dov’è la Libertà?

The other consideration is how we change the narrative around those who have already been inside. Recently I watched the 1954 Italian movie ‘Dov’è la Libertà?’ which translates to ‘Where is Freedom?’ Set in Italy in the 1950s, it’s a heart-wrenching tale about how a man who has served a 22 year sentence for protecting the honor of his wife, and is released back into society with only a few lire in his pocket (the Italian currency at that time). After his effort to reintegrate back into society fails due to being too honest for the real world, he attempts to break back into prison where he feels he can make his best contribution to humanity.

Although this film is set over 60 years ago, there are some striking parallels with the way that reforming US convicts are often thrown back into society with little or no support, and while it might be understandable that post-war Italy did not have the resources to create a meaningful reintegration program, we can’t make those same excuses today. This is especially true since it costs around $90 a night to keep someone incarcerated, so at least some of that budget needs to be kept aside for when they return to the world outside the prison walls. This can only happen if we see reintegration as a worthy investment, not just for the individual who has been incarcerated but for society in general.

Changing the Narrative

What happens when we change the narrative is that we get incredibly inspiring individuals who can contribute their knowledge and wisdom that they learned from their lessons and bring them back to enrich society as a whole.

An example of one such individual is ConBody CEO Coss Marte, who was released from prison in 2013 after serving time for dealing drugs. While in prison, Marte was told that even though he was only in his early twenties, with his weight and cholesterol so high, he only had five years to live. He lost seventy pounds in six months while he was in prison and is now the CEO of New York’s ConBody, a “prison-style boot camp” popular among celebrities and people from all walks of life, that exclusively employs former convicts. When Marte was asked how he had brought ConBody to life, he told CNBC Make It, “I never stopped pitching myself. I’d tell my story 20, 30 times a day. I’d go on the train and talk about what I do and act a fool. Whatever it took.” His story, and what it represented to others about the ability to change, was the key to his success, and to building a company that supports others like him and demonstrates how social change is possible.

Jarrett Adams is also another great example, turning a racially motivated wrong accusation into an inspiring story. He was wrongfully accused of sexual assault at the age of seventeen and sentenced to twenty-eight years in prison. While the evidence of his white accuser was unsubstantiated, as a person of color, he was still incarcerated. He devoted his time in prison to studying law and in a Now This video he shared how his studying enabled him to go from saying, “Hey look, I’m innocent, let me out,” to “Look, I’m innocent, this case supports my claim.” With help from the Wisconsin Innocence Project, his conviction was overturned. Adams walked out of prison with $32 to his name, but despite receiving no benefits or compensation, he became a lawyer and is fighting the wrongful convictions of others in his position with the New York Innocence Project. He said, “I won’t stop pushing forward. I have an opportunity with each day to continue to chip away at the negative stigmas that are attached to people who go to prison, whether rightfully or wrongfully.”

So this is how we start to change the narrative. By making prison into an opportunity for reform, growth and learning (whether in the face of a wrong accusation, or a right one). We have a long way to go yet—and in next weeks blog we will look at how we begin changing the narrative around the US prison system in general—but our starting point is definitely being prepared to challenge the common narratives that hold fixed perceptions of those who have committed crimes, and transform them into narratives of hope and possibility.

For the past decade, Sasha Allenby has been a ghostwriter for some of the greatest thought-leaders of our time. Her journey started when she co-authored a bestselling book that was published in 12 languages worldwide by industry giants, Hay House. Since then, Sasha has written over 30 books for global change agents. Following the events of the last couple of years, she turned her skill set to crafting social messages. Her latest book Catalyst: Speaking, writing and leading for social evolution supports thought-leaders to craft dynamic messages that contribute to change.