Reducing Economic Inequality Through Intersectionality – PART TWO

Reducing Economic Inequality Through Intersectionality – PART TWO

Read Time: 8 mins.

Economic inequality has a vast impact on a wide range of social issues.

In the first part of this article series, I was joined by Economist, Tech entrepreneur, and social activist Mammad Mahmoodi, where we discussed how extreme economic inequality is a relatively new issue historically; an issue which has increased substantially over the last 200 years. We also looked at how it exists on both a national level in the US, as well as on a global level. Additionally, we shared that the new paradigm in economics favors addressing this disparity in income inequality.

This second part will look very specifically at intersectionality and socio-economic gaps, while in the third part we’ll be sharing some practical solutions from economists around the globe.

We’ll start by lookin at three examples of economic inequality and intersectionality, which can be found in political representation, mass incarceration, and horizontal inequality.

Mahmoodi and Allenby finalizing the article series.

( I ) INEQUALITY AND REPRESENTATION

One of the largest issues of economic inequality lies in representation. Political representation has historically been skewed towards fairer rules and more abundant opportunities for the affluent. This is a problem globally but is also a very specific issue in the US for a core reason: US elections are fueled by external donations. The donors that are making the biggest contributions often do so because they want to operate within a system where their money is protected. This creates a vicious cycle where the wealthy back the candidates that make laws that will continue to protect that wealth.

Over $6 billion was spent on the 2012 US elections. In comparison, in the 2010 UK election around 49 million dollars was spent by the parties (an election’s greatest expense),1,2 while in Norway, the government pays over 60% of the candidate’s budgets, and each candidate is entitled by law to equal TV and radio time.3 In contrast, the US’ Citizens United Law was passed in 2010,4 meaning big corporations could act like citizens and make indirect participation to campaigns. Following the rise of Bernie Sanders in 2015, we’ve seen a whole generation of candidates that are refusing corporate and PAC donations. It’s a great start, but we need system-wide campaign finance reform on these policies moving forward.

In the US, this results in economic inequality worsening as candidates who stand for the disenfranchised are not receiving the same opportunities as those who stand for the economically empowered.

( II ) MASS INCARCERATION

Another significant issue in the US is mass incarceration. There is no equivalent in the modern world to the mass incarceration that exists in the United States. At any given time, over 2.3 million people are in prison in the US.5 This is almost 1 percent of the population, 12 times greater than the rate of incarceration in Japan.6

A person born in the lowest 10% of the US income bracket is twenty times more likely to go to prison than one born in the top 10%.7 In addition, having a family member in prison impacts first, and even second, degree family members8 not only emotionally, but also financially. Having a family member incarcerated, therefore, often bars other family members from climbing the poverty ladder too.

( III ) HORIZONTAL INEQUALITY

Horizontal inequality is a further factor. This is where those from a specific race, ethnicity, religion or region are significantly poorer than their peers. Research has proven that anywhere there is horizontal inequality in a society, there are higher rates of violence and destabilization within the society itself.9 For example, any community has a tendency of hostility towards those who are significantly poorer or significantly richer than them. This creates the great divide, leading to lessening opportunities to break out of socio-economic disparity.

INTERSECTIONALITY

Although we’ve focused on just three examples of the links between social issues and economic inequality so far (representation, mass incarceration, and horizontal inequality), there are countless further examples of social issues such as xenophobia, homophobia, homelessness, and racism which are directly linked to economic inequality. These impact one another simultaneously.

This is why intersectionality is of the utmost importance. Being a single cause activist without being aware of the other socio-economic parameters is not a sustainable way to solve issues. For example, Gloria Steinem highlighted10 that if we want the #MeToo movement to be sustainable, we need to ensure it continues to consider intersectional feminism and women of color. This was echoed by the Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository.11 As well as by British Comedian Jamali Maddix (who is most famous for his Vice TV series “Hate Thy Neighbor,” where as a POC, he went around interviewing Nazis to try and understand their psychology), who shared in his comedy show12 that the #MeToo movement has usurped racism. “Us black people have been waiting patiently in line. It was our turn. And then the #MeToo Movement swooped in and took our place,” he joked, on a recent stand-up comedy show in Brooklyn, NY, nodding once again to the need for more intersectionality in the social movements so we address all the issues simultaneously.

THREE MAIN CAUSES OF ECONOMIC INEQUALITY

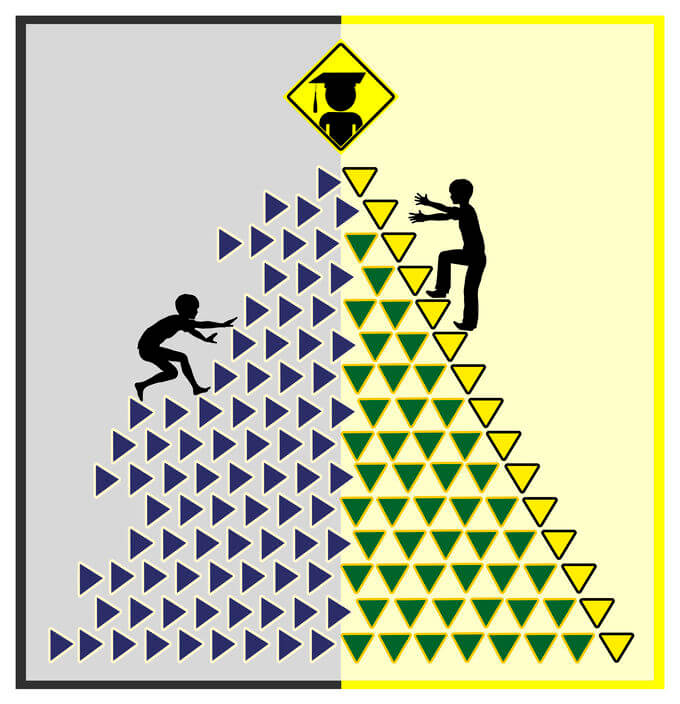

If we look more closely at the entanglement of these socio-economic issues, what we really need to address is the inequality of opportunities. What we are talking about is the fact that less economic mobility prevents individuals from moving up from their impoverished place in society.

In the US, three of the main causes of economic inequality are education, the justice system, and child poverty, which we discuss in detail below:

( I ) EDUCATION

Both the authors of this article series were raised in socio-economic disadvantage. Mammad Mahmoodi was raised in post-war Iran where—following the Iran/Iraq war—there were limited resources. Sasha Allenby was the daughter of a dock worker in an industrial town in the North of England, where the majority of employment comes from factories, and where the job market was unstable. However, in both their societies, being raised in economic disadvantage did not block them from accessing high level education and climbing the ladder of opportunities.

In contrast, lack of education opportunities is crippling to low-income communities in the US. If we divide education into three groups of: (i) Pre-K, (ii) K-12, and (iii) Higher Education, we begin to clearly see the issues of economic disparity and why they are insurmountable for many individuals.

NYC made free Pre-K available to all in 2013, but this is unique to New York and not echoed across the country.13

In K-12 the greatest issues lies in the quality of public schooling.With numerous instances of decline in K-12 public funding (either state or local), the burden of education is left on families.14,15

In higher education—which has become more essential due to a reduction of jobs in manufacturing because of automation—the biggest issue is costs that lead to young people starting their professional lives with heavy debts. In addition, government and state cuts on the education budget have made schools more expensive, adding to crippling student loans. In 2007 the average student debt was $19K.16 In 2013, it rose to $27K.17 By 2016 it increased to $37K.18 Further, in part one of this series, we highlighted that the government bailed the banks out in the financial crisis. They did so by giving the banks loans with only 0.75% average interest rate. In comparison, student loans carry an average 6.6% interest rate, putting further financial burdens on those who have had to borrow in order to study.

But what is even more startling in higher education is the disparity between the costs of college (including tuition, dormitory, textbooks, etc.) and the median income. In 1980, the median income was $46K and the average college cost was $9K per year. But in 2012, although the median income had only risen to $50K the average college cost has risen to $22K.19 That means there is a massive barrier for children from low to medium income families to attend universities.

( II ) JUSTICE SYSTEM

Low-income people are incarcerated at a much higher rate than their medium or high-income peers. If you divide the country into those in jail and those out of jail, the people who are in jail have less than half of the income of the people not in jail (even before they have been incarcerated).20 Much of this has to do with the unfairness and inherent biases of the justice system.

Justice has become a commodity that you need to be able to afford, rather than a right in the US. There are currently nearly half a million people awaiting trial in the US that are in jail without sentence because they—or their families—cannot afford the bailout money.21

This particularly impacts low-income people. NYCLU carried out a sample research on 8 counties in New York state and found that 10,000 people who spent time in jail before their trials had bailouts lower than $250, but as their families were unable to afford them, they had to remain in prison.22

Another example is the war on drugs, which started in the 1970s. It disproportionately addressed poor people23 (and especially poor people of color).24 It resulted in mass incarceration25 which has had a knock-on effect for the families involved, creating even fewer opportunities through the generations.

( III ) CHILD POVERTY

21% of children in the US live in poverty.26 This number increases to 40% for black children,27 (46% for black children28 under the age of 6), and 34% for Latinx children.29

Child poverty results in a range of issues which self-perpetuate. On a basic level, it means that food insecurities create lack of concentration for young people in places of education. It also leads to health issues (such as higher asthma rates for the economically disadvantaged)30 and learning disabilities (including increased autism rates for low-income communities)31 as well as limiting the access of underprivileged children to higher education.

The US Ivy League schools are a mirror of this social disparity. There are only 9% of the bottom 50% earners at Ivy League schools. Astonishingly though, in the top 50 to 75% of earners there are only 17% in Ivy League schools. That means that the children of the top 25% of earners dominate these schools with 74% of the pupils attending being from this group.32

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

Just about every country in the world was raised on the belief that the American dream is available to every US citizen. We all heard the story of the man or woman who came to the United States with $5 in their pocket and went from rags to riches by working hard and pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. But it seems that, in the current socio-economic climate, the American dream is not alive for all.

Integrational Income Mobility33,34 is an economic measure that is used to determine the extent to which income levels are able to change across generations. This measure determines the likelihood of any particular group being able to break out of their socio-economic limitations. In other words, it dictates whether, if your parents are poor, you will also be likely to be economically challenged. In comparison to other developed countries, US has one of the worst performances. For example, in the US, your future is three times more dependent to your parent’s wealth than it is in Canada or Scandinavian countries.35,36 This means that in the United States, if your parents are poor, you are much more likely to remain so yourself.

SOLUTIONS

Part Three of this series will present the solutions to some of the many issues we’ve highlighted. To summarize what those solutions might look like, we can draw from one of the most renowned economists of our time, Stiglitz, who shared that inequalities are “partly due to economic forces, but equally, or even more, they are the result of public policy choices.”37

Many of the policies and laws that have reinforced economic inequality include bankruptcy laws, unfair tax systems, tax loopholes, offshore tax evasions, inheritance laws, campaign finance laws, cash bailout laws, and intellectual property laws. In the third part of the series, we will break these down so that we can start to see some of the solutions to creating a fairer system for all.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Mammad Mahmoodi is an economist, community builder and tech entrepreneur. He has a passion for the social impact of technology, and how inequality impacts innovation and economic growth. He was co-founder of Ondamove (one of pioneering geo-tagging companies). Following that, he was a starter—and Executive Director—of Open Data Science Inc. (one of largest Artificial Intelligence communities in the world). He has taught entrepreneurship in a number of universities around the globe. Currently his main focus is supporting enterprises to create economic equality. He works and resides in Manhattan, NY.

Receive PART THREE of this series, plus regular blogs and updates. Be part of a community that is advocating for social change and learn to craft your messaging more effectively.

3. As Above

8. International Review of the Red Cross (2016), 98 (3), 783–798. Detention: addressing the human cost doi:10.1017/S1816383117000704

9. Stiglitz, Joseph E., Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them, W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., New York, 2013, P.289

19. Stiglitz, Joseph E., Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them, W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., New York, 2013, P.166

30. Stiglitz, Joseph E., Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them, W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., New York, 2013, P.179

31. As above

32. Stiglitz, Joseph E., Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them, W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., New York, 2013, P.180

37. Stiglitz, Joseph E., Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them, W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., New York, 2013, P.288